The Tehran Biennale was conceived as an independent counter-institution, a living experiment that reclaims art as a site of knowledge, resistance, and collective imagination within a country where creative expression is continually constrained by political repression and cultural isolation.

The project reimagines the historic Tehran Biennale, first founded in 1958 by Iranian-Armenian artist Marcos Grigorian, who, after visiting the Venice Biennale, envisioned a platform to situate Iranian art within an international dialogue. Supported by the Ministry of Culture, the original biennale was born from a desire to connect Iran’s artistic scene with the wider world. Yet, after the 1979 Revolution, that spirit of openness was dismantled, replaced by ideological control and institutional silence.

More than six decades later, my own encounter with the Sharjah Biennial 15 (2023), curated by Hoor Al Qasimi under the theme Thinking Historically in the Present, became the catalyst for reviving this lost lineage. What Grigorian initiated as an outward gaze toward Europe, Ghiasi reimagines as a non-Eurocentric platform, grounded in the Global South’s shared struggles and solidarities. The new Tehran Biennale, reestablished in 2023, transforms the biennale model from a showcase of nations into a tool of critique, decolonial imagination, and ethical world-building.

At its core, this project arises from urgent questions:

- How can meaningful art be produced within a system where cultural expression is trapped between commercialized orientalism for global visibility and state-sponsored propaganda for ideological control?

- How can Iranian artists, isolated by censorship and sanctions, engage meaningfully with the world while preserving the complexity of their lived realities?

- And how can one amplify silenced voices without colluding with the very structures that enforce their silence?

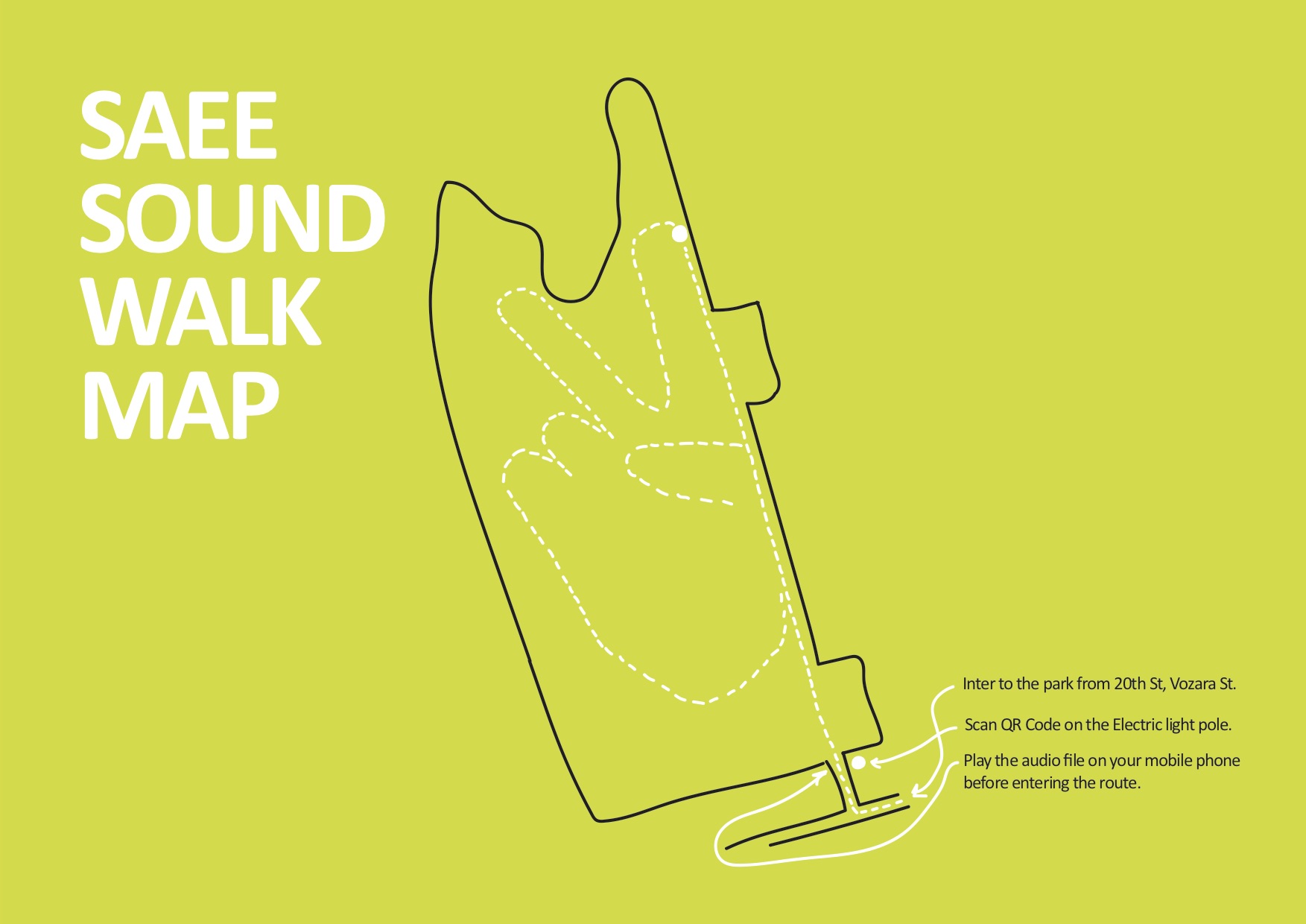

The first edition of the Tehran Biennale, held in May 2023, invited emerging artists to respond to the theme “Beyond the Horizon: Inventing the Reality.” Their works were installed across nontraditional and often hidden spaces, private rooftops, backstreets, and abandoned buildings in Tehran and Ahvaz, transforming the cities into dispersed sites of resistance. Each work intervened in public memory, confronting the erasures that have shaped Iran’s modern history.

By displacing art from institutional walls into ephemeral, lived spaces, the biennale not only reclaims public space but also challenges Eurocentric models of exhibition-making. It builds a horizontal network of artists and thinkers who operate beyond state and market control, an alternative ecology of art rooted in solidarity, fragility, and care.

In this context, the Tehran Biennale becomes more than an exhibition; it is a movement toward civil imagination. It honors Iran’s legacy as a cradle of art and culture while confronting the dystopian reality of its present. Through the intersection of history, heresy, and speculation, the biennale transforms isolation into dialogue, silence into speech, and art into an act of emancipatory world-making.